Spring and early summer in the Pacific Northwest bring splashes of vibrant color, warming temperatures, and the promise of sunshine. The collective spark of giddiness spreads, as the parks, gardens, and restaurant patios fill with people shaking off winter’s hibernation. After months of darker days with less activity and interaction, spring can feel like a swirling hive of high energy enthusiasm.

This shift, eagerly anticipated by many, can be surprisingly shocking and painful for those who are grieving. In the gray and rain of winter, it’s common for people to talk about feeling down or tired. The communal sense of feeling under the weather may help grieving people know they aren’t alone in having a hard time. When spring hits with its infusion of excitement, grievers often feel left behind, their sadness growing sharp in contrast to the messages of happiness coming at them from family, friends, and colleagues. While the world around them ramps up talk of impending summer plans for BBQs and vacations, people experiencing grief can feel even more more isolated and alone.

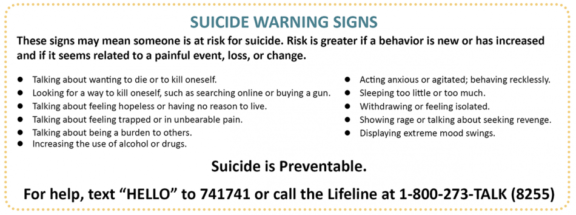

T.S. Eliot’s poem, The Wasteland, popularized the phrase, “April is the cruelest month.” His poetic view of the emotional toll that spring can bring is reflected in the nearly 15% rise in the rates of suicide in the months of May and June (in the northern hemisphere). In Oregon specifically, the rates are equally high throughout July, contrary to popular opinion—that December and the end of year holidays and consequent family pressures contributes to higher suicide rates at that time.

This yearly rise prompted researchers to search for clues for the contributors to this spike. Some refer to the “broken promise effect” where those suffering from depression are distraught when their moods do not improve with the onset of spring. Others point to physiological shifts, including the increase in energy that can come with more hours of daylight, and a concurrent decrease in the levels of melatonin in our bodies. The hypothesis is that this jolt of change can provide those who are severely depressed with just enough energy to plan and carry out suicidal actions. Additionally, some research points to a relationship between worsening depression and an increase in inflammation due to allergens from blooming flowers and trees. Researchers and practitioners have yet to settle on any one definitive cause for the rise in suicide rates during the spring, but the numbers support that spring and early summer can be a very challenging time for many.

Grieving children, teens, and adults who struggle with the dissonance between their personal grief and the general spring time ebullience can find support and validation in their groups at The Dougy Center. In these groups, they talk about how hard it can be to listen to people in their lives grow more and more hopeful and excited as the weather continues to improve. They help one another to know that it’s not unusual to dread the change of seasons or even feel resentful towards others who are experiencing joy with the advent of spring. They also share memories of spring break vacations and summertime holidays spent with the person who died. In all of this, they build connections and help to decrease the sense of isolation and separation that, while common in grief, can grow so apparent in this springtime season.